Big Research Funds Continue to Fight Huanglongbing Disease

$7 Million Multi-State Research Project Targets Citrus Threat HLB

UC ANR part of team led by Texas A&M AgriLife combating Huanglongbing disease

By Mike Hsu UCANR Senior Public Information Representative

Citrus greening, or huanglongbing disease (HLB), is the most devastating disease for orange and grapefruit trees in the U.S. Prevention and treatment methods have proven elusive, and a definitive cure does not exist.

Since HLB was detected in Florida in 2005, Florida’s citrus production has fallen by 80%. Although there have been no HLB positive trees detected in commercial groves in California, more than 2,700 HLB positive trees have been detected on residential properties in the greater Los Angeles region.

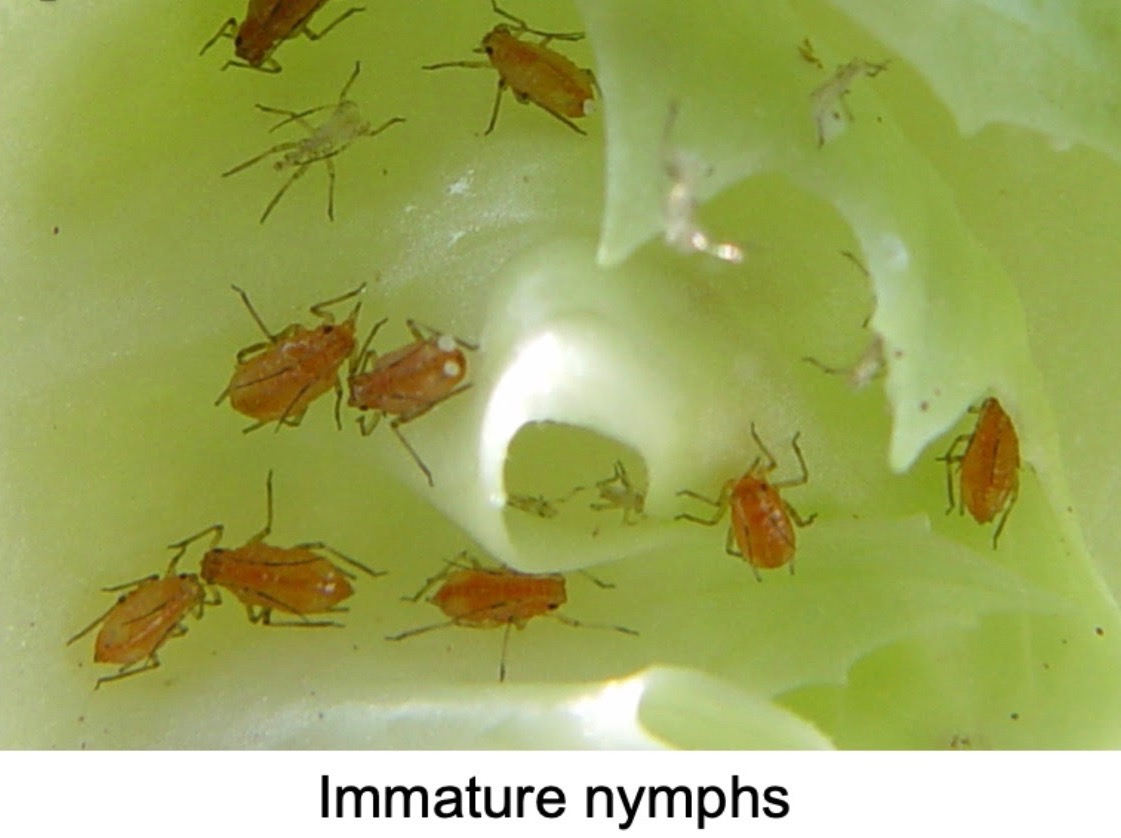

“It is likely only a matter of time when the disease will spread to commercial fields, so our strategy in California is to try to eradicate the insect vector of the disease, Asian citrus psyllid,” said Greg Douhan, University of California Cooperative Extension citrus advisor for Tulare, Fresno and Madera counties.

Now, a public-private collaborative effort across Texas, California, Florida and Indiana will draw on prior successes in research and innovation to advance new, environmentally friendly and commercially viable control strategies for huanglongbing.

Led by scientists from Texas A&M AgriLife Research, the team includes three UC Agriculture and Natural Resources experts: Douhan; Sonia Rios, UCCE subtropical horticulture advisor for Riverside and San Diego counties; and Ben Faber, UCCE advisor for Ventura, Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties.

$7 million USDA project

The $7 million, four-year AgriLife Research project is part of an $11 million suite of grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture, NIFA, to combat HLB. The coordinated agricultural project is also a NIFA Center of Excellence.

“Through multistate, interdisciplinary collaborations among universities, regulatory affairs consultants, state and federal agencies, and the citrus industry, we will pursue advanced testing and commercialization of promising therapies and extend outcomes to stakeholders,” said lead investigator Kranthi Mandadi, an AgriLife Research scientist at Weslaco and associate professor in the Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology at the Texas A&M College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

The UC ANR members of this collaboration will be responsible for sharing findings from the research with local citrus growers across Southern California, the desert region, the coastal region and the San Joaquin Valley.

“In addition to the ground-breaking research that will be taking place, this project will also help us continue to generate awareness and outreach and share the advancements taking place in the research that is currently being done to help protect California’s citrus industry,” said Rios, the project’s lead principal investigator in California.

Other institutions on the team include Texas A&M University-Kingsville Citrus Center, University of Florida, Southern Gardens Citrus, Purdue University and USDA Agricultural Research Service.

“This collaboration is an inspiring example of how research, industry, extension and outreach can create solutions that benefit everyone,” said Patrick J. Stover, vice chancellor of Texas A&M AgriLife, dean of the Texas A&M College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and director of Texas A&M AgriLife Research.

HLB solutions must overcome known challenges

An effective HLB treatment must avoid numerous pitfalls, Mandadi explained.

One major problem is getting a treatment to the infected inner parts of the tree. The disease-causing bacteria only infect a network of cells called the phloem, which distributes nutrients throughout a tree. Starved of nutrients, infected trees bear low-quality fruits and have shortened lifespans.

Treatments must reach the phloem to kill the bacteria. So, spraying treatments on leaves has little chance of success because citrus leaves’ waxy coating usually prevents the treatments from penetrating.

Second, while the bacteria thrive in phloem, they do not grow in a petri dish. Until recently, scientists wishing to test treatments could only do so in living trees, in a slow and laborious process.

Third, orange and grapefruit trees are quite susceptible to the disease-causing bacteria and do not build immunity on their own. Strict quarantines are in place. Treatments must be tested in groves that are already infected.

Two types of potential HLB therapies will be tested using novel technologies

The teams will be working to advance two main types of treatment, employing technologies they’ve developed in the past to overcome the problems mentioned above.

First, a few years ago, Mandadi and his colleagues discovered a way to propagate the HLB-causing bacteria in the lab. This method involves growing the bacteria in tiny, root-like structures developed from infected trees. The team will use this so-called “hairy roots” method to screen treatments much faster than would be possible in citrus trees.

In these hairy roots, the team will test short chains of amino acids – peptides – that make spinach naturally resistant to HLB. After initial testing, the most promising spinach peptides will undergo testing in field trees. To get these peptides to the phloem of a tree, their gene sequences will be engineered into a special, benign citrus tristeza virus vector developed at the University of Florida. The citrus tristeza virus naturally resides in the phloem and can deliver the peptides where they can be effective.

“Even though a particular peptide may have efficacy in the lab, we won’t know if it will be expressed in sufficient levels in a tree and for enough time to kill the bacteria,” Mandadi said. “Viruses are smart, and sometimes they throw the peptide out. Field trials are crucial.”

The second type of treatment to undergo testing is synthetic or naturally occurring small molecules that may kill HLB-causing bacteria. Again, Mandadi’s team will screen the molecules in hairy roots. A multistate team will further test the efficacy of the most promising molecules by injecting them into trunks of infected trees in the field.

A feasible HLB treatment is effective and profitable

Another hurdle to overcome is ensuring that growers and consumers accept the products the team develops.

“We have to convince producers that the use of therapies is profitable and consumers that the fruit from treated trees would be safe to eat,” Mandadi said.

Therefore, a multistate economics and marketing team will conduct studies to determine the extent of economic benefits to citrus growers. In addition, a multistate extension and outreach team will use diverse outlets to disseminate project information to stakeholders. This team will also survey growers to gauge how likely they are to try the treatments.

“The research team will be informed by those surveys,” Mandadi said. “We will also engage a project advisory board of representatives from academia, universities, state and federal agencies, industry, and growers. While we are doing the science, the advisory board will provide guidance on both the technical and practical aspects of the project.”

Project team members:

—Kranthi Mandadi, Texas A&M AgriLife Research.

—Mike Irey, Southern Gardens Citrus, Florida.

—Choaa El-Mohtar, University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Citrus Research and Education Center.

—Ray Yokomi, USDA-Agricultural Research Service, Parlier, California.

—Ute Albrecht, University of Florida IFAS Southwest Florida Research and Education Center.

—Veronica Ancona, Texas A&M University-Kingsville Citrus Center.

—Freddy Ibanez-Carrasco, Texas A&M AgriLife Research, Department of Entomology, Weslaco.

—Sonia Irigoyen, AgriLife Research, Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center at Weslaco.

—Ariel Singerman, University of Florida IFAS Citrus Research and Education Center.

—Jinha Jung, Purdue University, Indiana.

—Juan Enciso, Texas A&M AgriLife Research, Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, Weslaco.

—Samuel Zapata, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, Department of Agricultural Economics, Weslaco.

—Olufemi Alabi, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, Weslaco.

—Sonia Rios, University of California Cooperative Extension, Riverside and San Diego counties.

—Ben Faber, University of California Cooperative Extension, Ventura, Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties.

—Greg Douhan, University of California Cooperative Extension, Tulare, Fresno and Madera counties.