University of California, Division of Agricultural and Natural Resources

Pests and Diseases Cause Worldwide Damage to Crops

Pests and Pathogens Place Global Burden on Major Food Crops

By Pam Kan-Rice, UC Agriculture & Natural Resources

Scientists survey crop health experts in 67 countries and find large crop losses caused by pests and diseases

Farmers know they lose crops to pests and plant diseases, but scientists have found that on a global scale, pathogens and pests are reducing crop yields for five major food crops by 10 percent to 40 percent, according to a report by a UC Agriculture and Natural Resources scientist and other members of the International Society for Plant Pathology. Wheat, rice, maize, soybean, and potato yields are reduced by pathogens and animal pests, including insects, scientists found in a global survey of crop health experts.

At a global scale, pathogens and pests are causing wheat losses of 10 percent to 28 percent, rice losses of 25 percent to 41 percent, maize losses of 20 percent to 41 percent, potato losses of 8 percent to 21 percent, and soybean losses of 11 percent to 32 percent, according to the study, published in the journal Nature, Ecology & Evolution.

Viruses and viroids, bacteria, fungi and oomycetes, nematodes, arthropods, molluscs, vertebrates, and parasitic plants are among the factors working against farmers.

Food loss

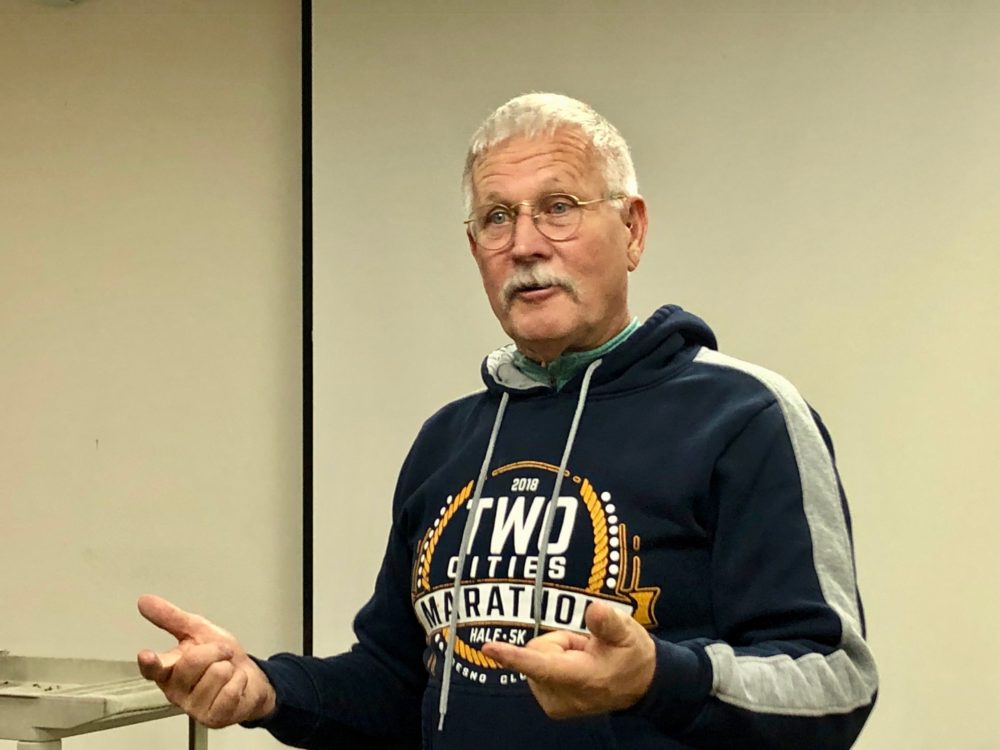

“We are losing a significant amount of food on a global scale to pests and diseases at a time when we must increase food production to feed a growing population,” said co-author Neil McRoberts, co-leader of UC ANR’s Sustainable Food Systems Strategic Initiative and Agricultural Experiment Station researcher and professor in the Department of Plant Pathology at UC Davis.

While plant diseases and pests are widely considered an important cause of crop losses, and sometimes a threat to the food supply, precise figures on these crop losses are difficult to produce.

“One reason is because pathogens and pests have co-evolved with crops over millennia in the human-made agricultural systems,” write the authors on the study’s website, globalcrophealth.org. “As a result, their effects in agriculture are very hard to disentangle from the complex web of interactions within cropping systems. Also, the sheer number and diversity of plant diseases and pests makes quantification of losses on an individual pathogen or pest basis, for each of the many cultivated crops, a daunting task.”

“We conducted a global survey of crop protection experts on the impacts of pests and plant diseases on the yields of five of the world’s most important carbohydrate staple crops and are reporting the results,” McRoberts said. “This is a major achievement and a real step forward in being able to accurately assess the impact of pests and plant diseases on crop production.”

The researchers surveyed several thousand crop health experts on five major food crops – wheat, rice, maize, soybean, and potato – in 67 countries.

“We chose these five crops since together they provide about 50 percent of the global human calorie intake,” the authors wrote on the website.

The 67 countries grow 84 percent of the global production of wheat, rice, maize, soybean and potato.

Top pests and diseases

The study identified 137 individual pathogens and pests that attack the crops, with very large variation in the amount of crop loss they caused.

For wheat, leaf rust, Fusarium head blight/scab, tritici blotch, stripe rust, spot blotch, tan spot, aphids, and powdery mildew caused losses higher than 1 percent globally.

In rice, sheath blight, stem borers, blast, brown spot, bacterial blight, leaf folder, and brown plant hopper did the most damage.

In maize, Fusarium and Gibberella stalk rots, fall armyworm, northern leaf blight, Fusarium and Gibberella ear rots, anthracnose stalk rot and southern rust caused the most loss globally.

In potatoes, late blight, brown rot, early blight, and cyst nematode did the most harm.

In soybeans, cyst nematode, white mold, soybean rust, Cercospora leaf blight, brown spot, charcoal rot, and root knot nematodes caused global losses higher than 1 percent.

Food-security “hotspots”

The study estimates the losses to individual plant diseases and pests for these crops globally, as well as in several global food-security “hotspots.” These hotspots are critical sources in the global food system: Northwest Europe, the plains of the U.S. Midwest and Southern Canada, Southern Brazil and Argentina, the Indo-Gangetic Plains of South Asia, the plains of China, Southeast Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa.

“Our results highlight differences in impacts among crop pathogens and pests and among food security hotspots,” McRoberts said. “But we also show that the highest losses appear associated with food-deficit regions with fast-growing populations, and frequently with emerging or re-emerging pests and diseases.”

“For chronic pathogens and pests, we need to redouble our efforts to deliver more efficient and sustainable management tools, such as resistant varieties,” McRoberts said. “For emerging or re-emerging pathogens and pests, urgent action is needed to contain them and generate longer term solutions.”

The website globalcrophealth.org features maps showing how many people responded to the survey across different regions of the world.

In addition to McRoberts, the research team included lead author Serge Savary, chair of the ISPP Committee on Crop Loss; epidemiologists Paul Esker at Pennsylvania State University and Sarah Pethybridge at Cornell University; Laetitia Willocquet at the French National Institute for Agricultural Research in Toulouse, France; and Andy Nelson at the University of Twente in The Netherlands.

UC Agriculture and Natural Resources researchers and educators draw on local expertise to conduct agricultural, environmental, economic, youth development and nutrition research that helps California thrive. Learn more at ucanr.edu.