University of California, Division of Agricultural and Natural Resources

Jamming Leafhopper Signals

Jamming Leafhopper Signals to Reduce Insect Populations that Vector Plant Disease

By Patrick Cavanaugh, Farm News Director

An innovative team of researchers at the San Joaquin Valley Agricultural Sciences Center, USDA Agricultural Research Services (ARS) in Parlier Calif., are trying to confuse leafhopper communication in hopes of reducing certain devastating plant diseases. Of particular interest is the glassy-winged sharpshooter, a large leafhopper that can vector or spread the bacteria Xylella fastidiosa from one plant to another which causes devastating plant diseases such as Pierce’s disease in grapes and almond leaf scorch.

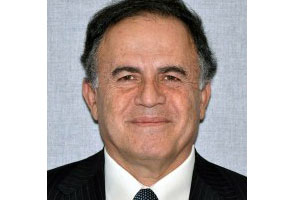

Dr. Rodrigo Krugner, a research entomologist on the USDA-ARS Parlier team since 2007, explained, “We started on this glassy-winged sharpshooter communication project about two years ago. These insects use substrate-borne vibrations, or sounds, to talk to, identify and locate each other; actually do courtship; and then mate,” Krugner said.

Click here to hear LEAFHOPPER SOUNDS!

“This area of research started probably 40, or 50 years ago with development of a commercially-available laser doppler vibrometer (LDV), a scientific instrument used to make non-contact vibration measurements of a surface,” Krugner said. “Commonly used in the automotive and aerospace engineering industries, the LDV enabled an entomologist to listen to and amplify leafhoppers communicating,” Krugner said. “We’ve been doing recordings in the laboratory, learning about their communication with the idea of breaking, or disrupting, that communication. Once we disrupt that, we can disrupt mating and thereby reduce their numbers in vineyards and among other crops.”

Krugner noted the research team is evaluating two different approaches: one is to discover signals that disrupt their communication, and the other is lure them away from crops or towards a trap. “We may be looking at female calls, for example. An analogous system would be the pheromones, or long-range attraction volatile chemicals released by female lepidoptera, to attract males.” However, since leafhoppers use only sound, Krugner said, “We’re trying to come up with signals to disrupt their mating communication. We’re also looking at signals to jam their frequency range, 4000-6000 Hz, so they cannot hear each other,” Kruger said. “We’re also looking at signals that can be used to aggregate them, or lure them, into one section of a crop, or maybe repel them from the crop. These are all different approaches that we’re investigating right now.”

Krugner explained, “Researchers are attempting to perfect the disruptive sounds in order to do the things we need—to actually implement a management strategy for disrupting not only glassy-winged sharpshooter, but anything in a vineyard that actually communicates using vibrational communication. We know what they are saying to each other, which is very important. In the laboratory, the signals that we have look promising in disrupting the communication of these insects, so we’re taking them into the field.

Current mating disruption trials are underway in Fresno State vineyards. “We’re going to finish that research, hopefully, next year,” said Krugner, adding, “usually, fieldwork takes two to three years to show something.”

(Featured photo: Rodrigo Krugner, research entomologist, USDA-ARS, Parlier)