By Patrick Cavanaugh, Editor

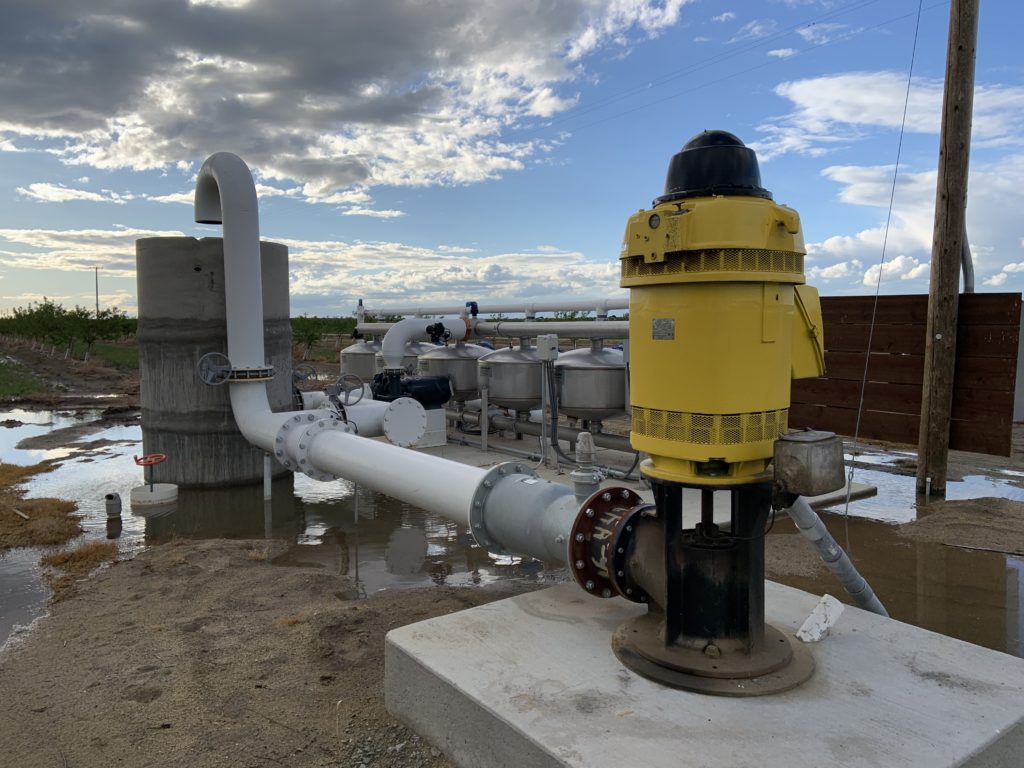

With the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) closing in on growers throughout California, there are many questions. One big one is that should growers go ahead and put a meter on their pumps? Helping the farming industry comply with SGMA is Chris Johnson, who owns Aegis Groundwater Consulting, based in Fresno. He’s recommending that growers put a flow meter on their pumps, but he does understand their hesitation.

“I think they’re concerned about what’s going to happen if they provide a mechanism where someone can come out and actually measure, record and evaluate how much water they’re using, that somehow that’s going to go against them,” said Johnson. “And the reality of it is, is that somebody might very well do that but they’re better off knowing that going in, they’re better off understanding and being able to manage and represent for themselves upfront.”

Now, currently we have the Groundwater Sustainability Agencies, which have finalized the Groundwater Sustainability Plans. “The Groundwater Sustainability Plans are the deliverable that the Groundwater Sustainability Agencies are tasked with. But you have to understand the scarcity of data we actually have to work with, to actually be able to make decisions,” said Johnson. “And as a consequence, what so many different GSAs are forced to do is to either accept existing data at face value, or they’re having to interpret what the data might be in the absence of actual functional information. And so, it may very well misrepresent what the basin as a whole is having to go through, and they may put restrictions on farmers and growers based on that. And so, that is where having your own data helps you defend your water use, helps you protect yourself.”

<PATRICK: I believe the online version of this article ended here. I would support that, in that the preceding text focuses on the importance of having specific data for individual wells. The following text is more a soliloquy on GSP’s and data gathering and validity.

Johnson explains what will happen when the sustainability plans are in place in 2020. “I think what will happen is once the GSPs are filed with the Department of Water Resources, there’s going to be a period of reflection where people are looking at the adequacy of information supporting the plans. There’s going to be outside parties that question the adequacy of the data and plans, and ultimately out of that will come the next step, which is, ‘Okay, now we have these in place, we know there are a lot of shortcomings.’ Let’s go fill in those gaps. Let’s go get this data together,” said Johnson. I think that most of the regulatory agencies recognize there are data gaps. Let’s just work through the process is there thinking.

“Let’s get ourselves to where we can now start collecting the data. So, in theory, what we’re going to see is over the next 20 years a refinement in all of this, as more information is available, as scientists and engineers get to provide analysis to the policy makers, we end up with a better product in the end,” Johnson noted.

But will that product be good for the growers? “That’s a difficult question to answer because better in the end is leading us towards answering a question with, you’ll have as much water as you want. Well, that’s unlikely to happen,” Johnson said.

“I think there’s going to be significant changes in how we grow things in the Central Valley. The consequence of that may be everything from less food coming out of the Central Valley and/or higher food prices as these businesses attempt to maintain some degree of solubility, so to speak, financially, trying to meet these limited resource. Because that’s essentially what we’re doing,” he said. “We’re coming back and saying : Something bad happened. Now, we’re going to limit this resource.”

The agricultural industry throughout California keeps pushing that it’s too important, we have to provide food for the nation and the world. “I think the more important way to look at this is, is that California can’t afford to have ag fail. And as a consequence, we have to find a means to meet all these different demands and do so in a way that helps keep ag moving forward. It just probably won’t look like what it does today,” he said.